Everything You Need To Know About Annie Ernaux, The Woman Who Just Won The Nobel Prize In Literature

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Annie Ernaux was not favored to win the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize in Literature. If you're wondering if people actually place bets on literature prizes, the answer is yes. Betting site Nicer Odds — a website that compares odds from a number of different outlets — had odds on writers ranked like racehorses. Brand names like Margaret Atwood and Stephen King had odds of 9/1 and 17/1 respectively while novelist Salman Rushdie was seen as the favorite with 13/2 odds on Tuesday, October 4, via The Guardian.

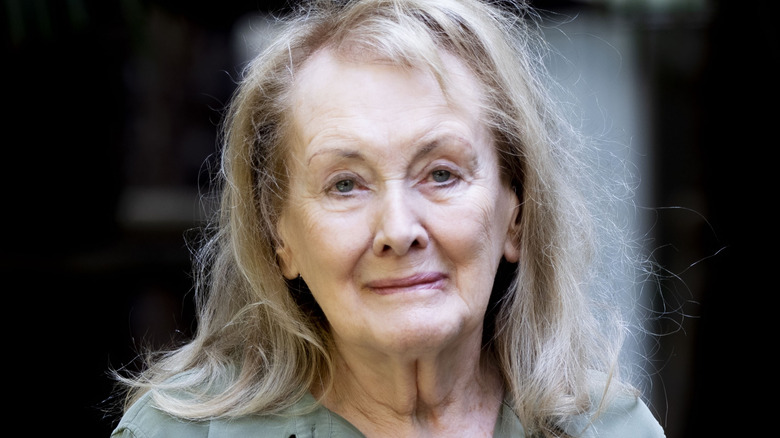

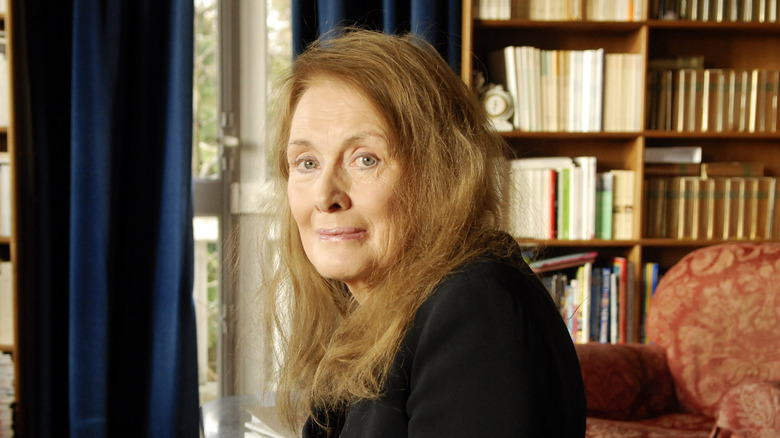

Ernaux, whose work spans decades, was ultimately given the award Thursday morning, making her the 17th woman to win the award, per The New York Times. While the committee was unable to get ahold of the 82-year-old French writer by phone, Mats Malm, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy — the committee that decides the prize — told The New York Times Ernaux did find out on the radio. When she did finally find out, Ernaux said during a press conference that she was "moved" by the award, adding that for her, "it represents something huge, on behalf of those I come from," a reference to her working-class upbringing, something "rarely dedicated in literature."

According to the Nobel Prize website, Ernaux's work won "for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangement, and collective restraints of personal memory." Those memories include fictional and first-hand accounts of illegal abortions and affairs examined through a minimalistic, raw, feminist lens.

Annie Ernaux is the first French woman to win a Nobel Prize in Literature

For some, the Swedish Academy's decision to choose Annie Ernaux for the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature was bold. Not only is she the first French woman to win the prize, but her American publisher, Seven Stories Press, told Reuters they felt it was brave for the academy to pick, "someone who writes unabashedly about her sexual life, about women's rights and her experience and sensibility as a woman."

Previous French writers who've won the Nobel Peace Prize in Literature include Albert Camus, who is best known for "The Stranger." The last French writer to win a Nobel Prize in Literature was the novelist Patrick Modiano in 2014.

Ernaux has written more than 20 books in her over 50-year career, most of which the Los Angeles Times reports are "short, chronicle events in her life and the lives of those around her." Ernaux doesn't shy away from any topic, touching on everything from sexual encounters to abortion.

Abortion is a topic that's especially important to Ernaux. When speaking to reporters on Thursday in Paris, Ernaux admitted that she didn't think that, once countries legalized abortion, it would be something she'd see the right to rolled back on, per Reuters. "Until my last breath," she told reporters, "I will fight for women's right to choose whether they want to be a mother or not." Ernaux shares her own abortion story through multiple books, including her first.

Annie Ernaux's first book was about her illegal abortion

When the Swedish Academy considers who should win the year's literature prize, they consider a writer's whole body of work. For Annie Ernaux, that work started in 1974 with the publication of her debut, "Armoires Vides," which became "Cleaned Out" when it was translated into English, via Reuters. "Cleaned Out" was Ernaux's first pass at excavating the experiences of, as her website explains, "her move from working-class to middle-class culture through education" — an experience that included an illegal abortion.

The fictional exploration wasn't enough. Ernaux revisited the abortion again in her book, "Happening." According to her United States publisher, Seven Stories, the book delves into a trauma Ernaux "never overcame," including the deep-rooted shame she felt, knowing following through with the pregnancy would force her family into social exile.

Shame, though, is something Ernaux has been familiar with her whole life. Born in Lillebonne Normandy to a working-class family, Ernaux attended a private, all-girls Catholic school, according to her website. It's Ernaux's membership in the working-class, rather than the middle-class of her schoolmates, that brought her "shame and milieu for the first time."

But according to The Guardian, it is Ernaux's complete lack of shame in her writing — particularly about sex, intimacy, and the women's experience as a whole. Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, agreed, saying on Twitter today that Ernaux's books had "lifted the veil on the intimacy of women with great modesty, but without embellishment."

Words are weapons for Annie Ernaux

Perhaps part of the reason Annie Ernaux's work is free of shame is because of her philosophy about writing. As The New York Times explains, Ernaux is a brevity queen, with each book "whittled down to an intense core — not a confession but a kind of personal epistemology." They add that what's central to her work is "an awareness that the most intimate moments of life are always governed by the circumstances in which they occur."

In a thread about Ernuax on Twitter, the Nobel Prize committee explained that for her, "writing is a political act." Language is a "knife" she uses to "tear apart the veils of imagination." By working at burning away this veil, Ernaux is able to save the "frail human details" and weave them into what The Guardian calls, "the story of a woman in the 20th century who has lived fully, sought out pain and happiness equally and then committed her findings truthfully on paper." They added that, "Her life is our inheritance."

Other critics, like writer Claire Messud, wrote in a 1998 review of Ernaux's work in The New York Times Ernaux was breaking the "demands of her genre — the desire for melodramatic intimate revelation and the smoothness of fictional tale-telling," adding that Ernaux's memoirs like "Happening" have a "searing authenticity" that "reveal[s] the slipperiness of much that we call memoir."

The truth about Annie Ernaux's affair with a married man

As important of a work as "Happening" is, Annie Ernaux's best-selling work in France is actually "Simple Passion," a fictional account of her affair with a younger, married man, per The New York Times.

But just like it took two passes to get to the truth of Ernaux's abortion story, "Simple Passion" was one attempt at understanding her relationship with a Soviet Union diplomat. The publication of "Simple Passion" was followed by Ernaux's recently-published "Getting Lost," the title for the "unaltered original journal" that according to a review in the New York Times, is "a love siege, a flood peak of existence" that Ernaux is unable to pull herself out of for over a year. According to The Times, an oft-repeated fear of Ernaux's is one many share: abandonment, of being tossed aside, of being humiliated by our own vulnerability. "I have no future, other than the date of our next meeting,” she writes in "Getting Lost."

Between the two accounts, The Guardian argues Ernaux's writing about her affairs "should be counted as one of the great liaisons of literature," alongside Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary. For The Atlantic, Alex Shepherd adds that "Simple Passion" is "a powerful depiction of being lost — or perhaps enveloped — by another person and ... possibly the best book about an affair ever written."

Annie Ernaux published more than one diary

Before she published "Getting Lost," the real diary pages she wrote during a tumultuous affair with a married man, Annie Ernaux's "The Years" came out in 2019 to international acclaim.

Shortlisted for the prestigious International Booker Prize, the work was called a "genre-bending masterpiece" that was giving autobiography a "new form, at once subjective and impersonal, private and collective." According to The Guardian, "The Years" spans the years 1940 – 2006, where Ernaux shares everything from the details of growing up working-class to her eventual divorce.

But all of Ernaux's work, fiction and memoir, are excavations of the experiences she's had examined on a personal and collective level because as much as she wants to trust her memory, she doesn't. As The New Yorker explains, Ernaux will often switch between first and third person, but referring to herself as "the girl of S," like in the case with her writing about the affair. Other times, she'll admit to the reader that she's gone too deep into a memory or when it's just gone completely.

Still, Ernaux covers both her own memories and both cultural and historical events including, "the pro-abortion rights manifesto of the 343 salopes, nuclear threat, the explosion of consumerism," among others, via The Guardian. In doing this, she demonstrates that memoirs — by women writers especially — dive deeper than "the small-scale, the domestic," and approach experiences from both a personal and collective perspective.