The Male Body: Ridiculous Things People Used To Believe About It

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

People didn't really know how the male body works for most of history. The differences between men and women were puzzling, leading people to come up with all sorts of wild and wacky theories about the male form. Thankfully, modern science has debunked a lot of the "wisdom" passed down by the ancients, and it's easy for modern, educated people to laugh at just how off-base some of the theories about the male body were.

Dissection of the human body was rare in ancient times, and was even outlawed by the Romans, which helps to explain some of the more outrageous conclusions drawn by our ancestors about the male body. Human dissection gradually became an accepted practice from the 14th century onward, which helped straighten some things out since scientists were able to actually look at how the human body is constructed. We have a lot more answers today than scientists had just a couple of hundred years ago, but science doesn't know everything yet. It remains to be seen whether or not some of our beliefs about the male body will be debunked by the science of the future, but, for now, these are some of the most ridiculous things that people have believed about the male body.

The act of penetration was reserved for manly men in ancient Rome

In some ways, the ancient Romans were a progressive people. While women in ancient Rome were considered to be inferior to men, they were, unlike in many civilizations throughout history, at least allowed to inherit and own property (although they were not allowed to control it). Since men were considered to be the superior gender, it was considered normal for a man to want to do the deed with other men. Having relations with one's wife was considered to be a man's duty in order to provide an heir, but it was common to seek out a male companion for pleasure.

In order to be considered manly, however, a man who wanted to engage in a bit of side nooky with another man could not be on the receiving end of things. "Being passive and being penetrated was considered women's work: men who submitted were considered deficient in vir and in virtus (virtue): they were denounced and reviled as effeminate," Paul Chrystal, author of In Bed With the Romans, wrote in a piece for History Extra.

Homosexual male encounters might have been normalized, but women weren't so lucky. "'Lesbian' sex often assumed penetration, which was considered man's work, so a woman adopting this role (and her submissive recipient) were castigated in equal measure," wrote Chrystal.

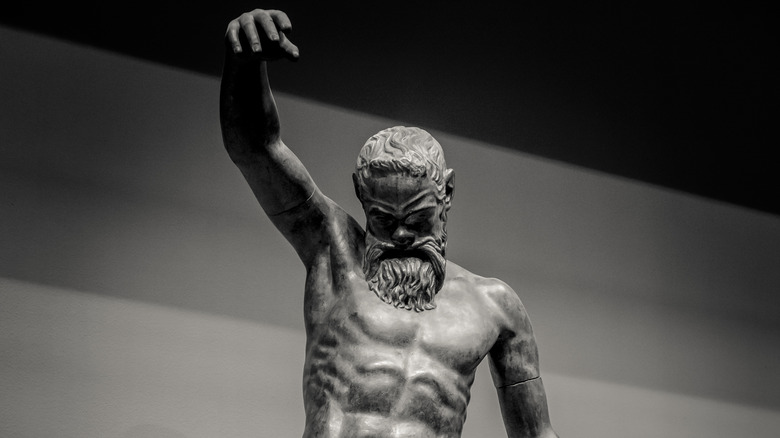

In ancient Greece, a large penis was thought to indicate a dishonorable man

If you've ever seen pictures of ancient Greek statues (or been lucky enough to view them in person) you may have wondered why a certain part of the male anatomy tends to be on the small side. The answer is that size matters quite a bit, or at least it did to the ancient Greeks. The size of a man's junk was directly correlated to his virtue, and the smaller it was, the better. "Greeks associated small and non-erect penises with moderation, which was one of the key virtues that formed their view of ideal masculinity," classics professor Andrew Lear told Quartz.

Idealized men, such as gods and athletes, were portrayed as packing less heat, whereas "decrepit, elderly men" and satyrs, (lecherous mythological creatures noted for their hedonism and debauchery), were depicted as being particularly well-endowed. It was thought that men who were on the smaller side were able to remain logical and rational, while those blessed (or cursed) with a sizable package were controlled by lust.

Victorian men grew beards to protect them from pollution

During the Victorian era, most men had a bushy beard. Far from being just a fashionable facial accessory, however, the beard served another purpose. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, which began in the mid-18th century, people in the 19th century were subjected to previously unseen levels of pollution. How were men of this time supposed to protect themselves from the filthy air of the city? Why, with a beard of course! Doctors advised their patients who were capable of growing facial hair to let their whiskers bloom in order to serve as a built-in air filter. Doctors also encouraged aspiring orators to grow beards, swearing that they could ward off sore throats and thereby enhance their public speaking skills.

The idea seems ludicrous today, but air pollution was out of control in the mid-18th century and people were desperate to protect themselves. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (via the Smithsonian), "By the 1800s, more than a million London residents were burning soft-coal, and winter 'fogs' became more than a nuisance." An exceptionally long-lasting fog in 1873 resulted in 268 deaths from bronchitis. Growing beards to keep pollution at bay might sound absurd, but it isn't actually so different from the more modern trend of wearing surgical masks in public to avoid contact with germs.

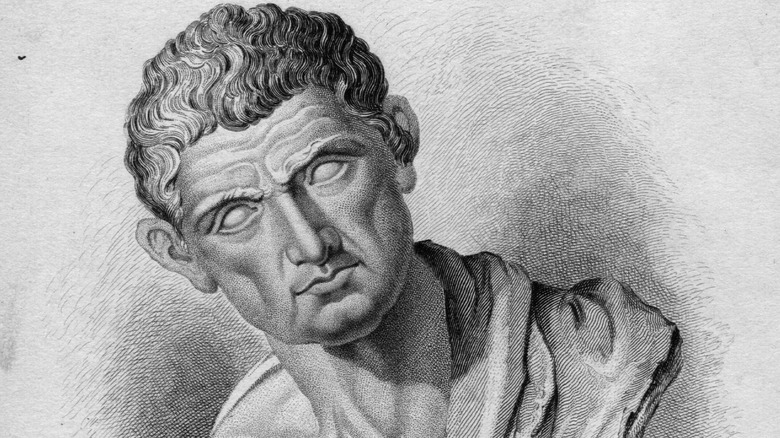

Aristotle thought that semen was converted from blood

Aristotle is another figure from the ancient world who is still highly regarded in modern times, although some of his theories were a bit out there — not to mention sexist. The Greek scientist and philosopher has influenced centuries of Western thought and helped to shape the world as we know it today. Aristotle founded formal logic, was the forefather of the study of zoology, and wrote about more than a dozen other fields, including biology, ethics, and political theory.

While knowledgeable in many areas, some of Aristotle's theories about the human body were a bit off the mark. Women, he declared, were essentially men, but had their genital organs located inside their bodies. To Aristotle (and the generations of thinkers his teachings influenced), women were nothing more than defective men.

Further proof of the inferiority of women was the fact that they do not produce semen. Here, too, Aristotle erred in his teachings. Aristotle believed that men are hot while women are cold. Based on this, he believed that men are able to convert blood into semen through their body heat, while women lack sufficient warmth to undergo this process and instead menstruate monthly.

Ancient Egyptian men were thought to carry semen in their bones

Aristotle might have been way off base when it came to what semen actually is, but he was far from the only one. The ancient Egyptians had a lot of wisdom (it takes that to build the pyramids), but they, too, had some misguided beliefs. Semen was a key part of the Egyptian creation myth. According to Egyptian mythology, Atum, the creator god, created the world through his seminal fluid. The twin gods Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture, also sprang forth from Atum's offering.

When it came to humans, ancient Egyptians were savvy to the fact that a man's testicles were involved in the baby-making process, and that life formed in a woman's womb, but, from there, things kind of fell apart. They believed that men stored semen in their bones and that the fluid merely passed through the testicles on the way out of the body.

Many cultures believed that excessive ejaculation would physically weaken men

While you won't go blind or grow hair on your palms if you engage in a little self-pleasure, these old wives' tales persist even into modern times. Warnings about the dangers of getting to know your nether regions go way back, and many people throughout history thought that men who engaged in the act were draining themselves of strength. Aristotle thought that self-indulgence could stunt a man's growth. In Medieval times, theologians postulated that evil women seduced men because they were bent on depriving them of their strength. In the 18th century, Dr. Samuel-Auguste Tissot said that losing one ounce of semen simultaneously drained a man of 40 ounces of blood.

People in the 19th century were so concerned about the dangers of one-handed love that anti-erection devices became hot market items. Doctors would resort to drastic measures, including electrically shocking a man's private parts, inserting needles, and applying acid, all to prevent them from spilling their seed and thus harming themselves. Corn flakes were originally developed by John Harvey Kellogg, a physician who believed that a bland diet could cure someone of the desire to self-abuse. Sylvester Graham had a similar thought in mind, believing that whole wheat was the answer. His invention of the graham cracker was part of an effort to quell sexual desire.

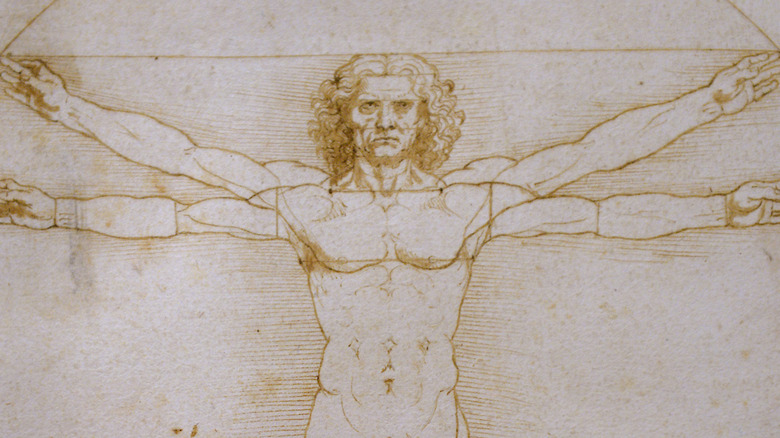

During the Renaissance, it was thought that only men were capable of great art

Throughout history, most of the prominent artists who have been widely acknowledged as masters have been men. While we often chalk this up to the institutional barriers that were in place for women for much of history, even in present times the vast majority of successful artists are male. To the enlightened mind, this indicates the ongoing marginalization of women in the artistic community. To others, it is proof of the Renaissance belief that women simply are incapable of the spark of genius that produces great art, making art the stronghold of men. "It was unthinkable for a female to become an artist," wrote Joanna Woods-Marsden in Renaissance Self-Portraiture. "Just as poetry, if we follow the logic of gendering in Western languages, was conceived as a masculine activity, so artistic creative powers were a male prerogative."

While there were, of course, many talented Renaissance artists who were female, the average person likely has not heard of female Renaissance artists Sofonisba Anguissola and Levina Teerlinc. Many male Renaissance artists, however, such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci remain household names in the modern era. Women, at the time, were considered to be inherently inferior. Talented female artists were viewed by their contemporaries as anomalies who had managed to overcome the limitations of their gender (via Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation and Identity).

In the 17th century, many thought that each sperm held a tiny human

In 1677, Anton van Leeuwenhoek changed the future of science forever when he decided to put his sperm under a microscope. Discovering what he called "animalcules" (what we call "protozoa" today) moving inside, he presented his findings to the Royal Society of London, which published his research in a journal the following year. Speculation about what, exactly, was living in the sperm ensued.

For roughly 200 years following van Leeuwenhoek's discovery, no one was exactly sure what sperm was, though they knew it was critical to create a baby. There were two major schools of thought in this time period on how babies were made. Epigenesists believed that both the male and the female contributed something to the baby-making process. Preformationists believed the "animalcules" van Leeuwenhoek discovered were actually miniscule, fully-formed humans just hanging out in sperm until they eventually grew to full size within a woman's womb.

The idea of preformationism didn't start with van Leeuwenhoek's research, though. The idea that babies were pre-formed in semen dates back to Anaxagoras, an ancient Greek philosopher. Van Leeuwenhoek's discovery of wriggling animalcules seemed to corroborate the idea that there were tiny humans living in sperm.

In Elizabethan England, it was believed that the male orgasm alone was not enough for pregnancy

These days, your average middle schooler can tell you how a human baby is conceived. A lot of factors must fall into place for a successful pregnancy, but, at the least, sperm from the father must unite with an egg from the mother. In Elizabethan England, people knew that you needed a man and a woman in order to create a baby, but they were a bit unclear on who needed to bring what to the party.

The orgasm was particularly important in Elizabethan England, as noted by GQ, because it was believed that it was necessary for both the male and the female to have one in order for pregnancy to occur. Thus, there was an incentive for a man trying to produce an heir to ensure that his lady was fully satisfied. On the downside, this meant that, among couples who were trying to avoid pregnancy, making whoopee was significantly more fun for the man (via His Last Letter: Elizabeth I and the Earl of Leicester). This not only left women trying not to conceive with the short end of the stick, but was also a wildly inefficient form of birth control.

An 18th century doctor advocated cutting off a testicle to produce a boy

There have been many old wives' tales throughout history that people have taken to heart in their attempts to determine their baby's gender. Advice to ensure your baby will be a girl includes eating lots of chocolate and trying to make a baby when the moon is full. If you want a boy, the hopeful future mother should sleep on the left side of the daddy-to-be and eat more red meat.

While following such folk wisdom hasn't been proven to be effective, it can be fun and is pretty harmless. In the 18th century, however, a far more painful method of trying to determine a baby's gender was proposed. Dr. Michel Procope-Couteau believed that by cutting off the testicle (or removing the ovary of a woman) that "corresponds by position — right or left — to the generation of a male or female," a couple could guarantee whether they'd produce a boy or a girl (via Monstrous Imagination). This advice harkened back to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates who believed that men produced sons from one testicle and daughters from the other.

Pliny the Elder believed that only men could be left-handed

Pliny the Elder is one of the most prominent figures of ancient Rome, but there's a reason that the Encyclopedia Britannica calls his magnum opus Natural HIstory "an encyclopaedic work of uneven accuracy." Natural History was regarded as the ultimate authority on science until the Middle Ages, but Pliny didn't always know what he was talking about. He did give modern historians insight into what Roman gardens were like and offered useful knowledge about agriculture, but he was also prone to presenting unproven claims as fact.

One of the things that Pliny got drastically wrong was on the subject of dexterity. Pliny said that most people are stronger on the right side of their bodies, although some are equally strong on the left and right. A chosen few are more skilled with their left hands, but this phenomenon is something that Pliny claimed "is never the case with women." Pliny's belief that only men can be left-handed is obviously erroneous. From Queen Victoria to Marie Curie, there have been plenty of left-handed women throughout history who have proven Pliny the Elder wrong.