Mike Rowe Opens Up About The New Season Of Dirty Jobs - Exclusive Interview

Mike Rowe is always up for a challenge. This new year, a special one has come his way: a reboot of the messiest, grimiest show we all know and love. "Dirty Jobs" is back, baby!

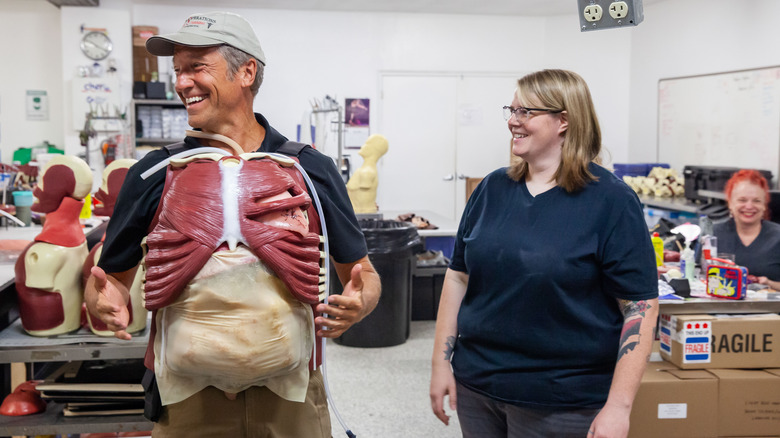

Truthfully, there's never been a better time for it. During a worldwide pandemic, essential workers are in higher demand than ever before, and businesses are desperate to get people back on their feet. When there's a job to be done, someone has to do it, and Rowe is ready to tackle whatever it may be. This season, we'll see him rod busting, epoxying floors, cleaning water towers, and even learning to perform combat surgery — and we got the chance to ask him all about it.

In an exclusive interview with The List, Rowe told us exactly what we can expect this season on "Dirty Jobs," revealed the scariest thing that's ever happened to him on set, and opened up about the impact that the show has had on him all these years.

Here's what we'll see this season on Dirty Jobs

What was your first thought when you heard "Dirty Jobs" was coming back?

God help me.

Really? [Laughs]

[Laughs] No, not really. I mean, I kind of knew it was going to happen shortly after the lockdowns kicked in, because it just seemed like everywhere I turned, there was reference to essential workers. "Dirty Jobs" was the granddaddy of essential working shows. Sure enough, fans and network people, they all were like, "Look, this is an opportunity to put this thing back on the air, because you've got your foundation now and it's focused on skilled labor and all of that." A lot of things sort of came together at the same time, so it made sense to do it. I don't know if it makes sense to do it for another eight years, but it definitely made sense to reboot the series.

What is this season going to look like compared to what we were seeing almost a decade ago? I can't believe it's been that long.

I know. Crazy. Well, the show itself hasn't changed. It's still a transparent look at an honest day's work through the eyes of an apprentice. That's me. We still do almost no pre-production, very little scouting. No casting. There's no acting. There's no scripts. There's no writers. We don't do second takes. We've never done second takes on that show, and we don't do it now, so the show itself is the same. The host is older than he's ever been, so things hurt a little more. But you know what? So do the fans, people who have been with that show for the last 20 years. I think they get it. We're all in a different place. That's really the biggest thing.

Our country has changed. Our relationship with work is different. And 11 million open opportunities, 11 million open jobs, that's new. $1.7 trillion in student loans, that's new. Our relationship with work overall, I think, is something that people are really interested in digging into, and "Dirty Jobs" gives us a great excuse to do that. It's still a show, first and foremost. Its job is to entertain and to have fun. It's not a lecture or a polemic or anything like that. But being where I am today, with my foundation and with the headlines being what they are, I just think it would be a missed opportunity not to wade in again.

What happens off camera on Dirty Jobs?

You said there's very little pre-production. What do you do to prepare for an episode of the show?

Pray. [Laughs] I mean, really, that's the beauty of this show. It's the genius, and it's the upside and the downside. The upside is I don't have to prepare at all. What I have to do is get on the right plane, get in the right Uber, get to the right job site, and show up. The reason I don't do any preparation is because I want it to feel like it feels for an apprentice who's going to his job or her job for the first time. I want the viewer to see me meeting the people that I'm going to be working with and for. I just think that's important. That means I don't have to waste any time prepping.

On the downside, it means we basically shoot from sunup to sundown. We don't really know when we're done because the work is never really finished, so it's a very physical show. We wind up showing you everything, more or less, that happens to me over the course of that day, so you can't cheat on "Dirty Jobs." You actually have to do the work, but you don't waste a lot of time beforehand trying to create some sort of fake reality. What you see is what really happens.

Like you said, you spend a whole day on a job site. What we're seeing in an episode is only part of the job. What kind of moments are viewers missing that you wish were included in an episode?

Well, it's still TV. No one really wants to spend a lot of time in the mundane reality of standing around waiting for the gas tank or the gas truck to show up so you can refuel the jackhammers or whatever that is. We acknowledge that's part of the job, but it's really just a question of how much time do you spend with each step of the process? For instance, in Nashville, I do a job called rock sucker, where I suck the rocks off the roof with a giant vacuum truck and this enormous hose. That is the bulk of the work. Now, we also have to drive the rocks around the neighborhood looking for somebody to take them because you can't just, you know, dump them in the street. That's kind of interesting, but the real work is sucking roughly 10 million rocks off of a flat roof with a giant hose.

Now, you can spend two minutes in TV time doing that, and you can get the message across, or you can spend about 15 or 20. We spend 20, because even though it's only that one beat, you can't articulate or illustrate the reality of that job unless you drag the viewer through it, and so we do. We don't always do it that way, but on that particular job, that was such a fundamental task that we just decided this is what we're going to make the whole show about. I even wrote a song, you know? It's "The Rock Sucker Song." [Laughs] Sometimes on "Dirty Jobs," there's nothing left to do but break into song. That happens this season more than once.

Mike Rowe reveals the hardest job he's ever had on the show

You've done seasons and seasons of this show, but I have to ask now that you have finished a new one: what is one of the most difficult jobs that you've done?

Oh. Well, there's typically — There's the dangerous column, the exhausting column, and the disgusting column. We got most of the disgusting stuff out of the way early in the run. Feces from every species, exploding toilets, right? Misadventures in animal husbandry. I've violated every barnyard animal I think there is. In fact, that's me right there [points to a photo behind his desk] artificially inseminating a turkey back in 2008, which is awesome.

Yeah. But I think, just in terms of [difficulty], the very first segment in the first episode on January 2, is rod busting. It's a team of construction workers that are really iron workers that only do one thing. They fabricate iron rods of rebar to build the skeletons and the infrastructure of a bridge or a tunnel or a road.

These guys, physically, they're just monsters. They work all day long busting rods, as they call it. They bend them, and they twist them, and they tie them, and they create these big, elaborate skeletons of work. They're really very beautiful. And then the cement trucks come in and cover everything with concrete, so nobody ever sees their work, but it's an essential part of the infrastructure. So yeah, first thing out of the gate, I spend a day with the rod busters down in Tampa, building an overpass, and they kicked my butt.

Really?

Oh, yeah.

Are there any dirty jobs that Mike Rowe wouldn't want to tackle?

A lot of these jobs that you do are — not even to be dramatic — life or death situations. Are there any jobs over the years that you've been hesitant to take on?

[Laughs] Well, yeah. All of them, maybe. There's a lot. A lot. I mean, that's the other thing about the show. Sometimes it's easy to look at a quick clip, and you might hear some dramatic music, and you might see a spectacular shot, and you might conclude from that, "Oh, Mike. He's a — you know, he's a stunt junkie. He's an adrenaline guy." No, I'm not. I'm a TV — I worked in TV for 20 years before I sold this show, and this show required me not to be a host, but to actually be the guest, really, like an avatar or a cipher. I only point that out because I'm not comfortable for a lot of the time. [Laughs] I'm not necessarily scared. I just don't quite know what I'm doing, and I'm often in environments where it takes a little getting used to.

You know, working at the top of a 2,000-foot radio tower, you've got to take a minute to get your head around it. Being lowered into the shaft of an opal mine in the Australian Outback that's 80 feet deep and as wide around as a manhole cover, that's a level of claustrophobia that, if you let it, I mean, it could make you crazy. So I'm often uncomfortable or not quite in my element. But the truth is I'm not paid on this show to get it right. I'm paid to try, so I never say no. I'll attempt whatever the job is.

Like I said, you know, in the early goings, we got a lot of the really super spectacular stuff out of the way visually. Now we've really settled into this place where it's like, "Look, there's so many great jobs out there that will allow people to prosper," and no one thinks about them that way. They just think of them as either dirty or dangerous or otherwise not appealing, but the show shifted back in Season 4, Season 5. This season, I think, is the best example where we can say, "Look, you're going to meet a lot of people making six figures a year doing something that looks like a vocational consolation prize." It's important, I think, to make that point, especially when you have so many open positions in our economy as we do right now. A lot of those positions are dirty jobs.

Here's where they find the dirty jobs they feature

How do you go about finding these jobs?

Well, when we started, I had a list of about 20 that I wanted to do. "Dirty Jobs" was this real simple tribute to my granddad. It was supposed to be three one-hour specials, and it got out of control. People saw those early episodes, and they wrote to me. They didn't write to me to say, "Oh, you're terrific," or "Oh, this show is so great." They wrote to me to say, "You ought to come and meet my dad, my brother, my cousin, my uncle, my sister, my mom, right? Wait until you see what they do." That's when I realized, you know what? This is a very personal show. It's personal for me to start, but it's also personal for the viewer because they see themselves sometimes in me, and they see themselves in the people that we profile.

So what I did after I finished those first couple dozen or so, I just opened a chatroom — this was before Facebook was a thing — and just said to the fans, "Look, you do it. You program the show, you know? You tell me what the job is, where the job is, and why I should do it, and I'll take all that to the production company, and we'll be in touch." In that way, the hosts of "Dirty Jobs" became the people we profiled, and the programmers became the viewers. That's a long way of saying that's where we get our ideas from, the people who watch the show. It's always been that way.

That's really special. Is there any job that hasn't been profiled on the show yet that you would like to try?

No. [Laughs] I mean, really, I'm sure there are jobs out there that I haven't done, but we passed that point a while ago. The truth is "Dirty Jobs" was never really about the dirt or about the job. It was about the people. You'll run out of jobs eventually. You'll certainly run out of industries.

The first time I went in a coal mine, it was amazing. We learned a bunch of stuff. It was a bituminous coal mine in Pennsylvania. And then a couple months later, I thought, "You know what? That was so good. Let's go into an anthracite coal mine. Let's see the difference." And then that was so good. I thought, "Well, let's go into a bauxite mine. Now let's go into a borax mine. Let's go into a copper mine. Let's go into a gold mine. Let's go into an opal mine." So we wind up doing nine shows on mining.

The same thing happened with fish boats. The crab boat was exciting. I bet a lobster boat would be fun. How about a haddock boat? Suddenly, we started doing a lot of similar jobs that had important differences. But mostly, it was the people. It was, "I want you to meet this guy because what he does is not only interesting, but it impacts you." As long as I can draw a line between the guy in the opal mine or the rod buster or the skull cleaner or the golf ball retriever, or fill in the blank, as long as I can find a way to make it relevant to you, the viewer, that's what the show is.

Anyway, no, I don't have a list of jobs somewhere that I'm dying to try. But I'm still standing by to hear about sponge divers. I mean, somebody said, "What about sponge diving?" I said, "Where do we go?" They said, "Tarpon Springs, Florida." I said, "Okay. I'm there." Two weeks later, we're free diving for sponges. I'm sure there are other jobs like that out there I just haven't heard about. I'm just not looking for them. I'm just waiting to see if somebody brings them and if the network says, "All right. Go do it."

He reveals what some dirty jobbers think of others

It's interesting that you brought up "this mine leads to this mine," because jobs do build up on each other. I think going down that link and that line of jobs, you can find some ones that you didn't even know exist and kind of explore from there.

Always. Yeah. Robert Frost said, "Way leads onto way," and it's very true, in my business, anyway, especially when you're affirmatively looking to build on the last thing you did. That's the other great source for "Dirty Jobs" beyond the viewer, is the last dirty jobber. I would always ask, "Where should I go now?" They would always have suggestions.

The other interesting thing about the people that we profile was you'd be amazed how appalled and shocked many of them are at what other people do on the show. It's like the crab fisherman would say, "Man, when you went in that opal mine, that was the craziest thing I ever saw. I would never do that in my life." Meanwhile, the opal miners are saying, "You're out there on that crab boat. Are you out of your mind? I would never do anything like that." So within the community of dirty jobbers, you have people who are consistently baffled by the jobs that we feature. That's kind of cool, too. It really is a mosaic. One day, I'm making blueberry pies with a bunch of sweet little old ladies up in Maine, getting covered in jelly, and the next day I'm in a grease trap with a giant vacuum hose, once again socking my way to the next job.

Mike Rowe shares his scariest experience on the show

People get injured doing these jobs, too. I know that you have broken bones and you've gotten stitches from doing them. What's the worst injury that you've had on "Dirty Jobs"?

I think the thing that scared me the most actually happened back late in Season 2. I was with a farrier, a blacksmith, out in the middle of a field somewhere. We were making horseshoes and shoeing horses out in the field. He had this little blast furnace about the size of an oversized toaster oven, made out of iron. It got very, very hot inside, and that's what you'd use to forge the steel.

Anyway, I was about to light it, and I noticed there were two slits on either side of it. I thought, "Oh, you know what? It'll be cool to get one of those artistic shots." I had my cameraman on one side, filming very, very tight through this little slit. So what you see is my eyes rise into the shot, and then I turn the igniter, and then a little flame comes up inside, and it goes, [Makes a "whoosh" sound] like that. So it's one of those cool, high-speed shots that I thought would just be fun to get. Well, the cameraman was trying to get his focus, and the gas had already been turned on, and so, like, 10 seconds go by, and some gas built up. More gas built up inside this thing than [it] should've. When I turned the igniter, [Laughs] what you see in slow motion is a wall of flame about three feet long go [Makes another whooshing sound], and it wraps around my head very, very quickly. And it singes my eyebrows, burns off my eyelashes, and fused my contact lenses to my eyes. I wasn't sure what happened. All I knew was when I blinked, it made a sound that it normally doesn't make. [Laughs] So I'm like, "Okay." I ran over to the truck. I got in front of the mirror, and I just picked these little pieces of plastic out.

The doctor said later, "It's a good thing you were wearing them. They actually protected your eye." So I was fine. But it was just one of those stupid little moments, where, you know, you do have to be super, super, super mindful all of the time on a show like this because you're not just in hazardous environments. You're making TV, which makes you stupid. Study after study shows making TV will make you stupid. You think you're on camera, so you think you're safe, and you got your crew to worry about. They're all around you, too.

Yeah. We have many, many stories of minor calamities that plagued us during the course of the show. Thankfully, nothing truly tragic.

Well, I have contacts, too. That makes my stomach just flip.

Yeah. It's sickening.

Here's how Dirty Jobs originally got started

What drew you to entertainment in the first place, and how has your perspective changed through your journey on "Dirty Jobs"?

I mean, the honest answer is a 300-page book I can't get around to finishing. But the truth for me is the show is very, very personal. It started as a tribute to my granddad, who dropped out of high — Well, gosh, he dropped out of the seventh grade and went to work, but by the time he was 30, he was a licensed electrician, a contractor, a plumber, a steam fitter, a pipe fitter. He could build a house without a blueprint. He was ingenious.

This show was a tribute to him. I grew up right next to him. I was his apprentice when I was a kid, and I thought I'd follow in his footsteps. But the truth is that handy gene is recessive. [Laughs] And I just didn't get it. So, upon his advice, I got a different toolbox. I got into the entertainment business not because I loved it. Frankly, I wasn't interested in it at all. I wanted to do what he did, but I couldn't. It was kind of like one of those kids on "American Idol" when they realize for the first time in their life, "No, it ain't going to be you, dude. By the way, you can't sing. [Laughs] So figure something else out." That's what entertainment was for me.

I went to a community college. I studied singing and acting and writing, English, a lot of stuff that I really wasn't that into. Then I started narrating nature documentaries, and then I started impersonating a host, and then I really got into the business. I had probably 300 jobs before "Dirty Jobs." That show happened because my granddad turned 90, and my mother called me and said, "Michael, wouldn't it be great if before he died, your grandfather could turn on the TV and see you doing something that looked like work?"

Whoa.

I know. Brutal. I went right across the bay here in San Francisco. I went into the sewer with a cameraman the next day and profiled a sewer inspector. What I really learned from that, to answer your question, that's when my education actually started. That's when I stopped impersonating a host and started being a guest. That's when I started letting the viewer see me try and fail.

What Mike Rowe learned after he started filming Dirty Jobs

As I started to do the show, what I realized was, on a personal level, that I had become disconnected personally from a lot of things I had grown up with. A lot of things I took for granted, a lot of things I'd learned from my Pop: where my food came from, where my energy came from, how so many industries connect us all. Dirty industries. It was kind of an eye-opener for me to realize just how disconnected I had become from the things that I really used to value.

I figured, "Look, if it happened to me, it can happen to you." It can happen to anybody. Anybody who walks in the room and flicks on the switch and isn't gobsmacked by the fact that the lights come on or blown away by the fact that they flushed the toilet and, you know, they can wave goodbye to their poop, right? If we're not blown away by those things, then we've become disconnected from some really important stuff. Sorry, that's a long answer, but that's the truth of it. For me, "Dirty Jobs" was a reminder of where my bread's buttered and who's doing the work.

And I think, to some extent, the lockdowns reminded people, too, right? I mean, this little conversation we're having right now is made possible by wires and pipes and cables and people who tend to those things. I don't know about you, but I'm on a first-name basis with my Amazon Prime driver, my UPS driver. All those jobs suddenly become important.

So, look, the goal of "Dirty Jobs" is to entertain you and make you smile and make you think. But the purpose is to tap the country on the shoulder and say, "Don't forget about her. Don't forget about him."

Things we usually take for granted. I didn't even know a lot of these jobs existed, but they have to. They've always been there. This year I've had to figure out technology, like Zoom. I'm not a technology person, but someone is. They made the computer. Like you were saying, it's just things you don't usually think about.

I didn't know what Zoom was a year and a half ago. I thought it was a verb, right? Literally, three weeks after we were locked down, I'm sitting where I'm sitting right now, hosting the first Zoom TV show to go on the air anywhere. It was "After the Catch," the captains from "Deadliest Catch." We did nine of those things. And then my Facebook show, "Returning the Favor," we did 18 of those long distance. It forced a lot of people to pivot or perish, really. I mean, here we are. We're still figuring it out.

Will there be more seasons of Dirty Jobs to come?

Are we going to be able to see more of "Dirty Jobs" after this new season?

Well, I doubt that the network is ever going to stop airing them. It's one of the few genuine reality nonfiction shows that holds up forever in reruns, so it'll be out there.

Are we going to do more than the six that we just shot? I'm open to it. To be honest, I swore I'd never do another one after 2012.

Really?

Yeah, because I had made my point. We did 300. We shot in every state multiple times, and I felt like that was good. We had a great run. I'm doing it again now because the headlines have made the show relevant in ways that I don't think the network anticipated. I certainly didn't anticipate it, so it's rare to have an opportunity.

I'm doing a show on Fox Business called "How America Works." I'm doing "Dirty Jobs" on Discovery. I'm running the mikeroweWORKS Foundation in between. I have a certain amount of permission now, I think, to talk about the things that matter to me, and the TV shows allow that to happen. I don't want to be the guy that climbs back into the ring and just says, "I'm going to try one more time." It's not about that. It's just about saying, "All of this stuff suddenly feels connected. Maybe it'll be useful, helpful maybe, to somebody."

A brand new season of "Dirty Jobs" premieres Sunday, January 2 at 8 p.m. PST/EST on Discovery.