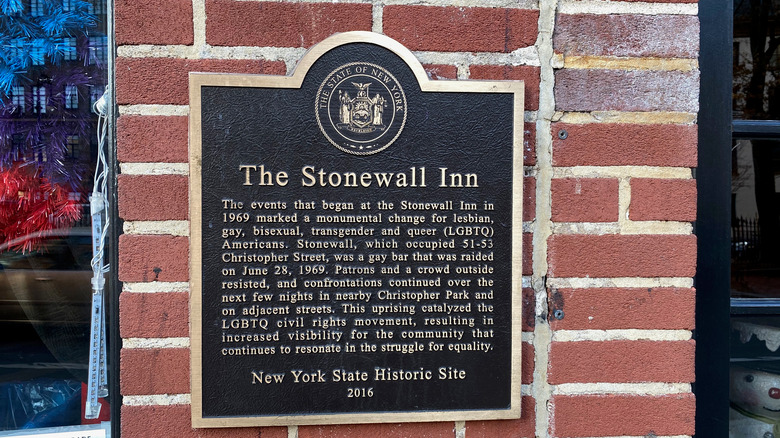

What You Should Know About The Stonewall Riots

The Stonewall riots were an important turning point for the gay rights movement in the United States. The riots, also termed the Stonewall Uprising, took place over the course of six days in June 1969 and they helped to pave the way to liberation for LGBTQ+ individuals. But you probably already knew that the Stonewall riots came at an important and pivotal moment in American history. However, there's much more to know about the riots than just the time and place. For example, while it was undoubtedly an important event in America's queer history, it absolutely was not the beginning of the gay rights movement, nor was it the first rebellion against discrimination in a gay bar.

So, what exactly is the significance of the Stonewall riots? This dive into history will tell you everything you need to know about what happened during the uprising, and the progress that was made in its wake.

The Stonewall Inn was a Mafia-owned 'dump'

The Stonewall riots took place at a bar called the Stonewall Inn in New York City. The establishment, which is still operating on Christopher Street in the West Village and is now considered a historical landmark, was owned and operated by the Mafia– specifically, the Genovese family (via History). PBS noted that it, like other Mafia-run taverns of the time, served overpriced, watered-down drinks and did not make much of an effort to be a comfortable setting.

When speaking to The New York Times, Stonewall patrons described the bar using words like "dump," "hellhole," "dirty," and "sleazy," before going on to list other gay bars in the city that were much nicer. But as Jerry Hoose, a founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, told PBS, "The bar itself was a toilet, but it was a refuge, it was a temporary refuge from the street." So while the Stonewall Inn did not provide ideal accommodations — nor running water — it was a place where members of the queer community knew they could go and feel at ease.

Life for LGBTQ+ individuals before Stonewall

At the time the Stonewall riots took place in 1969, homosexuality was criminalized, at least in some fashion, in most states. That meant that the majority of people who were gay or gender non-conforming could not live openly. However, in the years preceding Stonewall, some progress had been made by gay rights activists.

For example, up until 1966, it was still illegal for bars and restaurants to serve a gay patron alcohol — in fact, the mere gathering of gay people was considered "disorderly" illegal conduct, per History. A gay rights group called The Mattachine Society staged a "sip-in" at a bar called Julius', which got the ball rolling in overturning the law, according to The New York Times. But it was still illegal to engage in any kind of affection with members of the same sex in public, such as holding hands, dancing, or kissing. This necessitated places like the Stonewall Inn.

The bar was operated illegally as it didn't have a proper liquor license, but it served as a place of refuge as it was one of the few gay bars that allowed same-sex dancing, illegal though it was. Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt, an eyewitness at Stonewall, told PBS, "The Stonewall was totally different because you could slow dance together. Holding on to another person without that fear that someone is going to bash you over the head is totally centering. So going to the Stonewall grounded me and then the Stonewall riots just brought that feeling out into the real world."

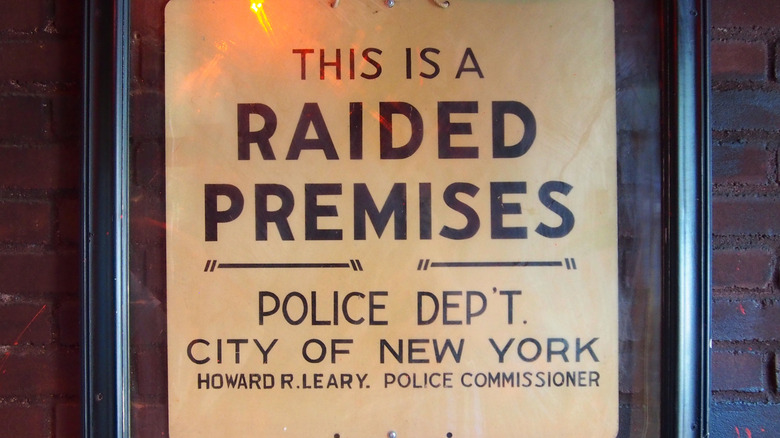

Police raids at gay bars were a common occurrence in the 1960s

Though the Stonewall Inn provided a space for members of the LGBTQ+ community to gather, that didn't mean they were always safe. The police regularly raided the bar and others like it, despite the fact that the owners of said bars usually had the police on their payroll. According to the book "Stonewall," historian and author Martin Duberman estimated that NYPD's Sixth Precinct collected $2,000 per week from the Stonewall Inn (via Slate). Still, raids were common — sometimes because the cops wanted more money, sometimes because a bar wasn't being discreet enough in its illegal activities, and sometimes because the politicians in charge wanted more public goodwill for cleaning up "crime."

History noted that corrupt police officers often tipped off the owners of Mafia-owned gay bars before raids so they could hide the alcohol. Additionally, a white light bulb hanging from the ceiling of the Stonewall Inn warned patrons of an impending raid, so dancing couples could separate and avoid being arrested for what was deemed "lewd conduct," per PBS.

But no such warning came on June 28, 1969.

A standard police raid was met with resistance in June 1969

Very early in the morning on June 28, 1969, the NYPD raided the Stonewall Inn. However, this raid would not be like previous gay bar raids that patrons had come to expect, wherein people were arrested and alcohol was seized. That morning, things were different — bar patrons resisted arrest and refused to disperse instead of remaining outside the bar to protest the unfair treatment of the queer community. Objects were thrown and, at one point, the police officers on the scene barricaded themselves inside the bar, while protesters outside tried to burn down the building (via History).

A raid had been conducted on the Stonewall Inn just a few days earlier on June 24, and the second raid may have followed as a result of the owner's comments to police, according to Slate. The owner told Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, who led the raid, that they'd be open again the next day, which may have led the officer to become determined to shut the place down.

Pine was reportedly more interested in taking inventory and seizing the alcohol present at the bar but arrested individuals who did not cooperate. Pine later told PBS that bar raids of this nature usually took "maybe a half hour to clear the place out," but that didn't happen on June 28. Slate noted that the raid took longer than usual, and patrons under arrest became agitated.

Judy Garland's death wasn't the precipitating event that kicked off the riots

So why was the June 28, 1969 raid so much different than the ones that preceded it? One popular story claims patrons at the Stonewall Inn were inspired by their grief over beloved star Judy Garland's death, whose funeral had taken place a couple of days prior. However, that's been thoroughly debunked by the people who were there (via The New York Times). What actually caused patrons to fight back that fateful night? The truth is, no one really knows whether something out of the ordinary sparked the rebellion but more importantly, Stonewall was the result of mounting frustration after years of discrimination, which was likely amplified by the fact that there had been a raid at the same bar just a few days earlier, coupled with the atmosphere of challenging authority that had been happening all throughout the '60s, per Slate.

Still, one of the rumors surrounding Stonewall that does actually has some truth to it is the idea that the protestors formed a Rockettes-style kickline — though participants are quick to point out that it was actually multiple kicklines, accompanied by singing and chanting.

So, who threw the first brick at Stonewall?

One of the most common questions surrounding the mythos of the Stonewall riots is who threw the first brick? Marsha P. Johnson, a drag queen and activist, is often credited as being the one to get the riot started, but that claim has been debunked by Johnson herself, who told The New York Times the raid had already started by the time she got to the Inn.

Johnson's friend and fellow activist Sylvia Rivera is also sometimes credited for the brick-throwing or tossing a Molotov cocktail, but she has also denied this. It's also been said that Stormé DeLarverie was responsible, which she sometimes confirmed and other times denied, so it's inconclusive (via The New York Times). In fact, there's been some doubt as to whether any bricks (or Molotov cocktails) were thrown at all — though objects definitely were thrown, whether they were glasses or shoes or rocks from outside the bar.

But the focus on who "started" the Stonewall riots really misses the point. As queer writer Chrysanthemum Tran wrote for Them, "Stonewall and the movement it sparked was, at heart, a collective uprising — one that cannot be attributed to a single person or small group of people." The Stonewall riots happened because an entire community pushed back against oppression and discrimination, not because of one person's individual choices.

The riots and activism continued

The Stonewall uprising continued for nearly a week after the initial riot on June 28, 1969, according to History. CNN reported that an estimated 2,000 people gathered outside the bar the following night to engage in public acts of affection and riot.

According to Slate, the riots flared up in earnest for the final time the Wednesday after the initial uprising, when a write-up in the Village Voice, a local newspaper, gave the event objectionable coverage. According to the Village Voice, some protesters marched on the newspaper's offices, which were close to the Stonewall Inn.

Much of the protests and activism that took place after the first night occurred in the Village. The New York Times reported that on the last night, some participants set fire to garbage on Christopher Street (where the Inn was located) and the nearby Waverly Place. The neighborhood, which was known for being the "center of gay life" according to participant and activist Jerry Hoose, had already been a hub for activism, but the Stonewall riots allowed organizers in the area to take it to the next level (via PBS). As Hoose recalled, a group of people handing out leaflets on Christopher Street for a meeting in the wake of the riots "were planning a meeting that night to form a more militant organization," which would go on to become the Gay Liberation Front (GLF).

How media coverage played a role in the Stonewall uprising's historical and political significance

Much of the initial media coverage surrounding the Stonewall riots was unkind and even incited further protesting. The Village Voice's coverage of events inspired the most backlash — perhaps because the Village Voice was so close to the Stonewall Inn that columnist Howard Smith could see the bar's sign from his desk at the Voice (via PBS). Smith became an eyewitness to the events because when he went down to the Stonewall Inn after seeing the commotion happening from his window, he ended up getting barricaded inside the bar with the NYPD. He was the only journalist to have witnessed what happened inside the bar that night. Another reporter from the Voice, Lucian Truscott IV, covered what was happening outside the bar. Both accounts utilized offensive language to describe the queer people involved in the rebellion, as did other publications, like the New York Daily News.

Despite the media's use of slurs and indelicate language to describe the riots, activists intentionally sought out news coverage. "Part of what is important about Stonewall is that it gets a certain amount of straight recognition," historian Hugh Ryan told The Washington Post. He recalled Jim Fouratt, a protester and co-founder of the Gay Liberation Front, telling him, "The first thing I did when I got home from Stonewall is I picked up my Rolodex and I called everyone." And "everyone" included reporters and other activists to keep the momentum going.

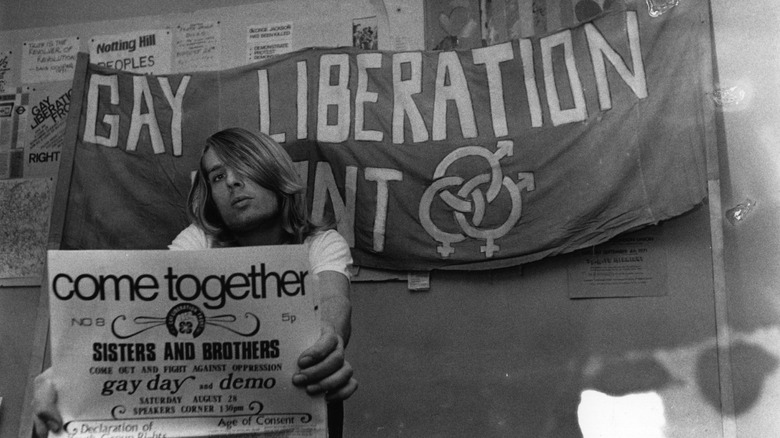

The Gay Liberation Front and other activist groups were formed in the days after Stonewall

The Gay Liberation Front, a gay rights organization, "was born from the ashes of Stonewall," according to Mark Segal, a member of the group who recalls handing out leaflets on Christopher Street (via ABC News). In an interview with PBS, Jerry Hoose recalled being there the night the organization was officially named. "It was insane! There were 50 or 60 people and we couldn't even decide what to call the group," he explained. He continued, saying, "But before the night was over we came together with GLF — the Gay Liberation Front."

Other organizations were also formed in Stonewall's wake, including the Gay Activists Alliance, per the Library of Congress. Such organizations worked tirelessly to change political and social conditions for the queer community. One of the memorable ways in which they did so was by organizing Christopher Street Liberation Day.

Stonewall became the starting point of the first pride parade

The first gay pride parade, known as the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day march, took place on June 28, 1970, one year after the events of the Stonewall uprising. The march in New York City started from the Stonewall Inn, and marchers made their way up to Central Park (per NBC). They didn't have a police permit, according to The New York Times, but by the time they got to Central Park, they'd drawn a crowd of at least 1,000 participants (though the exact number is up in the air). Marchers proudly declared their sexual orientation, shouted gay liberation slogans, held hands, and kissed (via National Geographic). To this day, the NYC Pride March passes by the Stonewall Inn along its route.

Activists coordinated with organizers in other cities to hold marches in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago. Other cities, like Boston, followed with their own parades the next year in 1971, per The New York Times.

Stonewall's legacy

The increased activism and recognition of the gay rights movement that Stonewall brought in its wake helped activists to push for more legal protections and make progress politically, per History.

The Stonewall riots have since attained national name recognition — President Barack Obama even mentioned the riots in his inaugural address (via The Atlantic). And in 2016, he designated the Stonewall National Monument to honor the movement for LGBTQ+ equality. And, of course, Pride marches are still held in cities across the world.

But it's important to remember that, as JSTOR Daily noted, the Gay Rights Movement didn't start with the Stonewall riots — nor was it the first riot. Rather, the uprising was the first to be commemorated publicly and turned into a national event thanks to media coverage and activism. Stonewall is an important turning point in the struggle that had been ongoing for many years at that point. So while the Stonewall rebellion was an important moment in the fight for equal rights for the LGBTQ+ community that we should certainly commemorate, it is also vital to pay tribute to the work of the countless activists and organizers who fought before, during, and after the Stonewall riots of 1969.