Surprising Traits Men Found Attractive Throughout History

Beauty standards have a tendency to go in and out of style. What was considered attractive a hundred years ago might be considered positively revolting by today's standards. Women throughout history have been subjected to both beguiling and bewildering ideals of beauty, and taking a look at some of the things that were considered beautiful through the ages proves just how arbitrary beauty standards truly are.

Some of these traits are quite mystifying and will make you wonder just what people of the past could possibly have been thinking. Other historical beauty standards, however, will have you wishing that our modern standards of beauty were as open-minded as those of our ancestors. For better or worse, these ideals of beauty shaped the lives of women across the ages. From ancient Greece and Rome to Renaissance Europe, these are some of the most surprising traits men have found attractive throughout history.

Ancient Greeks idealized the unibrow

Frida Kahlo might have sported a now-iconic unibrow in the 20th century, but her fashion statement went against the grain of modern beauty standards. While many people thought she was flouting more modern ideals of beauty, she was actually embracing a centuries-old tradition. To the ancient Greeks, nothing was more attractive than a woman with just one eyebrow.

Like Kahlo, ancient Greek women did not just let their unibrows grow freely, but would also take pains to make them even more prominent. They would highlight the hair just over the bridge of the nose by applying cosmetics to either enhance an existing unibrow or create the appearance of one. While unibrows aren't typically considered attractive in modern times, thicker brows are making a bit of a comeback. Model and actress Cara Delevingne, for example, doesn't sport a unibrow, but her thick and full eyebrows helped to spark a modern trend for a bushier brow.

Spartan women kept their hair short

Those familiar with the tale of the Trojan War know that Helen, the Spartan queen whose affair with the Trojan prince Paris led to bloody war between their two kingdoms, was famed for her beauty. Sparta was considered to be a land of beautiful women, but the beauty standards were far different back then from what you might expect today.

The historical Helen, who would have lived roughly 3,500 years ago during the Bronze Age, would have, as a queen, had tattoos of red suns on her chin and cheeks. Her hair would have also been shaved when she was in her teens, and, when it grew back, would have been arranged to look like snakes. In classical Greece, which began in the 5th century B.C., Spartan beauty standards had changed a bit. Men kept their hair long and styled it, but women were expected to cut their hair off upon marriage and to keep it short for the rest of their lives.

Crimson fingernails were greatly admired in ancient Ireland

In ancient Ireland, a woman's worth often came down to what her hands looked like. While light skin and golden hair were also prized, it was a woman's hands that revealed whether or not she came from a good family. The ideal hands were "well-formed, with slender, tapering fingers" according to A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. Beautiful nails were also a must. Women of the upper classes were expected to have rounded, well-kept nails. Even among the men in ancient Ireland, nail grooming was considered mandatory. It was considered to be shameful for men of the upper classes to have unkempt nails.

Today, many of us consider the color green to epitomize Ireland, especially on St. Patrick's Day, but those desiring a more historical Irish look on the holiday might want to pass up the shamrocks in favor of red hues. The color red was favored in ancient Ireland, and many women would dye their nails, as "crimson-colored fingernails were greatly admired."

High foreheads were a must during the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Many women in modern times debate over whether or not they should cut bangs, often to make the forehead seem smaller. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, however, it wouldn't have even been a thought since high foreheads were considered de rigueur. In the 14th century, fashion-forward women began to pluck their hair to raise the hairline. While this gave them a higher-looking forehead, the original purpose behind the hair plucking was less about a high forehead and more about creating an oval face shape. Considered to be an elegant and beautiful look, the obsession with face shape gradually morphed into a desire for tall foreheads.

By the Renaissance period, women were taking drastic measures to achieve a high forehead. Simple plucking gave way to rubbing at the hairline with a rough stone, and even burning off unwanted hair with a chemical called quicklime. Women also removed most of their eyebrows, making their foreheads appear even larger.

Black teeth were a symbol of beauty in Japan

Japan is no stranger to fashion trends that may seem unusual to people in the west. In modern times, many women pay for a look called "yaeba," which is essentially getting dental work to create a crooked smile. The trend is thought to make women more approachable by making their smiles less perfect. To accomplish this, false teeth are attached to a woman's original teeth.

This isn't the first time that Japanese women have altered their teeth for the sake of beauty. Before yaeba, blackened teeth were long considered to be attractive. The practice was called ohaguro, and it dates back to the Kofun period, which lasted from 250 to 538. Bones dating back to that time show evidence of tooth blackening. The practice didn't become widespread, however, until the end of the Heian period, around the 12th century. Ohaguro continued through the Edo period in Japan and began to die out towards the end of the 19th century, although some other Asian cultures still practice tooth blackening.

Pale skin and prominent veins were essential during the Renaissance

Forget tanning. Women during the Renaissance were all about pale skin. Light skin was considered to be beautiful not necessarily for the aesthetic quality, but because paleness served as an indicator of status — someone with a light complexion was sufficiently wealthy to not have to work outdoors. In Elizabethan times, the obsession with light skin was so great that women would resort to extreme methods, such as bloodletting, to create the perfect pallor. Others, including Queen Elizabeth I herself, would apply a powder made of lead to their faces. This had the effect of lightening the skin, but also slowly poisoned the wearer.

The perfect skin tone was not just pale, but practically translucent. The more clearly the veins could be seen through the skin, the better. Some women even took to drawing blue lines on their skin in order to give them the appearance of prominent veins.

Tiny, dainty feet were all the rage in China for centuries

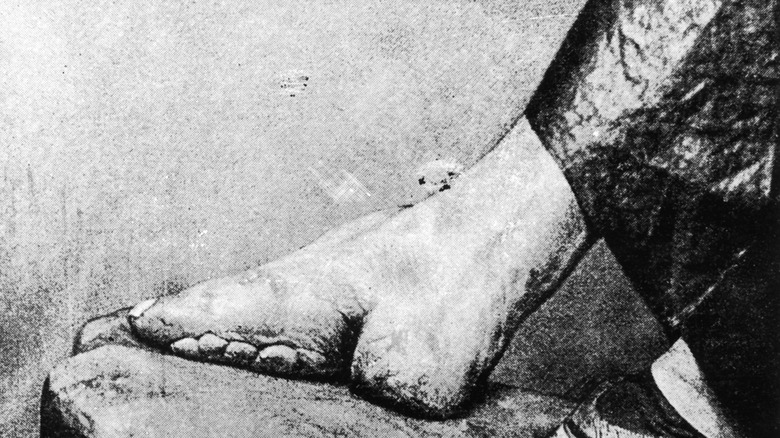

In China, an obsession with tiny feet turned grisly in the 10th century. Small feet were so highly prized, especially among the upper classes, that girls would have their feet bound to achieve a "Golden Lotus" foot no more than three to four inches long. The process was cripplingly painful — literally. Young girls would have their four smaller toes bent under their foot and tightly bound, permanently deforming the foot and impeding its growth. The process was not only excruciating, but also dangerous. Women could easily lose toes to infection. The bindings and deformed shape of the foot made it incredibly difficult to walk, but improved a girl's marriage prospects.

The practice of foot binding went on for centuries. While there were many attempts to ban the practice, public outcry was so great that foot binding went on until the early 20th century. It was permanently banned in 1912 after the Chinese Revolution toppled the Qing dynasty and created a republic.

A prominent stomach was desirable during the Renaissance

The Western ideal of beauty has trended towards slimness for more than a century, but for a stretch of time full-figured women were in vogue. Renaissance painters such as the 17th century Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens painted beautiful, and often sensual, women with ample flesh upon their bones, and his works are still celebrated in modern times. Today, the word Rubenesque is still used to refer to voluptuous women. While many modern women desire to have a flat stomach, the Rubenesque ideal favored a thicker mid-section – rounded stomachs were considered the height of femininity.

During the Renaissance, larger women were considered particularly beautiful. Voluptuous curves were viewed as a sign of wealth, and in Italy were also thought to be a sign that a woman would bear healthy sons. While we often think of corsets primarily as a way to achieve a waspish waist, they were also used to accentuate the bosom and hips and to give less-endowed women the appearance of substantial curves.

Limping ladies were the height of fashion in Victorian England

Victorian England was quite the interesting place. One of its greatest trendsetters was Alexandra of Denmark, wife to the Prince of Wales. She would go on to become his queen consort when he took the crown as Edward VII of Great Britain in 1901, but before that, she would set one of the most bizarre fashions in history. Renowned for her beauty, people were eager to follow Alexandra's example. When rheumatic fever left her with a limp, women were quick to copy it. "A monstrosity has made itself visible among the female promenaders in Princes Street," wrote the North British Mail in 1869 (via the BBC). "It is as painful as it is idiotic and ludicrous."

In order to properly execute a limp, women first began to wear mismatched shoes, causing them to hobble along in what would come to be called the "Alexandra limp." This gave rise to shopkeepers selling shoes with mismatched heels. When the fashion finally died out, it was replaced with something equally crippling: the hobble skirt. Hobble skirts were deliberately tight around the ankle, forcing women to take small strides, each one threatening to throw them off balance.

Mustached women were prized in 19th century Iran

Many ladies fight a constant battle against facial hair. Since we typically consider facial hair as a masculine trait, women who have a little fuzz of their own often remove it or bleach it. Roughly one in 14 women have a condition called hirsutism which is characterized by "excessive" hair on their bodies appearing in a "male" pattern. Even women who don't meet the criteria for hirsutism, though, can struggle with unwanted body hair and feel pressured to remove it.

If those women had been living in 19th century Iran, however, it would have been just the opposite. During the Qajar period, a thin mustache was considered the height of female beauty, and women would even apply a dark shadow above their upper lips with makeup to achieve the effect. The end of the Qajar era in the 1920s also saw the end of the era of the mustache being a female beauty standard in the region.

Early 20th century women were expected to be frail

In the 1920s, the feminine ideal of beauty was a woman who looked like she was on the verge of passing out at any moment. Linda Lin, a psychologist at Boston's Emmanuel College, explained to Daily Burn that "femininity was tied to frailness, weakness and vulnerability" a century ago. "Power, strength and muscularity were thought of as masculine traits, and gyms were for bodybuilders and athletes," she said.

Even as recently as the 1960s, strenuous exercise was viewed as something that could damage a woman's health. It wasn't until the 1990s that the idea of a toned, muscled woman began to be considered not only acceptable, but also attractive. While being toned in modern times is considered aesthetically appealing, the new standard isn't necessarily an improvement over the old one. "The culture is defining what's attractive, and it's not more accepting," said Lin. "Now women can feel bad if they don't have the right muscle tone."