How Women's 'Perfect' Body Types Changed Throughout History

How do we determine what makes a person beautiful? Though it might seem like the standards of beauty we have today must be historically universal, really the opposite is true. The "perfect" female (and male) body has greatly changed over the years, even though the foundation of the female form has stayed the same.

So, next time you feel like your own body might be less than perfect, just remember that "perfection" is an ephemeral ideal, bound to change and transform — looking stunningly different from one generation to the next.

The Paleolithic era

One of the earliest examples of art that's ever been discovered, is also a primitive symbol of an idealized woman. And she doesn't look at all like the models of today. The Venus of Willendorf — a statue crafted somewhere between 24,000-22,000 BCE — is a paradigm of fertility.

This girl goes way beyond curvy. In fact, she's a little on the heavy side. Featuring large breasts, large hips and a healthy stomach, it's clear that a good body equalled one that could bear many children. The model has no face — pretty eyes, or bright red lips were clearly not a priority at the time. A big healthy body was all that mattered because you were your own method of survival. You couldn't bat your long lashes at a mountain lion to make it go away, you had to be strong!

As a piece of art, it's likely that this figure is greatly exaggerated from what the women of the era actually looked like, but that further proves that "voluptuous and well-nourished" was the ideal 25,000 years ago.

Ancient Greece

The Greeks were defining beauty literarily, thanks to 8th-7th Century BC author Hesiod, who "described the first created woman simply as kalon kakon, [which meant] 'the beautiful-evil thing'. She was evil because she was beautiful, and beautiful because she was evil." Being a hot guy back then? Lucky! Being born a bombshell Grecian lady? Not so much! Ancient statues show us artists' idealized form, which for women featured largish hips, full breasts, and a not-quite-flat stomach. But the Greeks were defining more than just "beauty" — they were nailing down the math of attractiveness.

Plato gets the credit for originally endorsing the Greek-born "golden ratio," as the bar by which all beauty is subconsciously judged, but it was his colleague Pythagoras, who came up with the ratio for beauty — in faces, and in nature. (Remember the Pythagorean theorem? That.) Put simply, he found that in order to be considered "beautiful", women's faces should be two thirds as wide as they are long, and both sides of the visage should be perfectly symmetrical. Symmetrical faces continue to be regarded as more beautiful today, so send your hate mail to "P'thag" if you're rocking — and owning — that asymmetry.

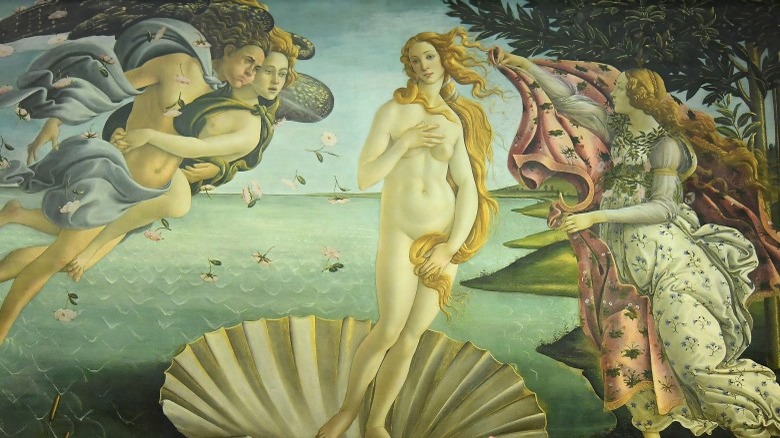

The early Renaissance era

The artists of the Renaissance wanted to move away from the modesty and strict religious values of the Middle Ages. So from 1300-1500, they started painting naked breasts that symbolized a mixture of fertility and sensuality.

The idealized women of artists like Raphael were commonly curvy, pale but with slightly flushed cheeks, and soft, round faces. Raphael admitted that most of his paintings were not based on real models, simply his imaginings of what a beautiful woman would look like. This was true for many painters. With the Renaissance began a transition — from simply considering women to be objects of fertility, to objects of lust and beauty.

The Elizabethan era

Queen Elizabeth was crowned in 1558, ushering in the era of makeup. Having derived from a society, which, according to one Harvard paper, deemed a woman with a face-full of makeup to be "an incarnation of Satan," the 25-year-old queen liberally slapped on the face paint — and that signature red lip. This trending makeup routine quickly became a symbol of class at the time. The paler you were, the higher your status. Poor people had to work outside and get terrible tan lines, so the wealthy would show off their pale skin as a symbol of opulent indoor living.

Also wanting to maintain her virginal image (and later hide her smallpox scars) in addition to flaunting her status, Elizabeth painted her face with a thick coat of white lead-based powder, and lip rouge. Members of high society followed suit, likely due to the belief that lipstick "could work magic, possibly even ward off death," according to the paper. Not one to bail on her own brand, Elizabeth died, wearing "a half-inch of lip rouge" on her pout.

Post French revolution into the late 18th century

After the French rebelled against the aristocracy during the French Revolution in 1789, the people wanted to distance themselves from their disgraced royalty. Makeup became much simpler and the insanely ornate gowns of the very rich were paired down. Though their dresses would seem pretty fancy for us today, it was a much more wearable and mobile way of dressing than in the past.

Before the revolution, makeup was worn equally by men and women. As the idea of "artifice" found disfavor in society, both sexes opted for more natural looks. But as memories of the revolution began to fade, and the country entered the 19th century, makeup for women in court gained popularity again.

Though it was still criticized by some, the art of putting on makeup and getting dressed for the day became a sort of show that coquettes would perform for potential admirers. Elite women would literally invite spectators to watch them primp in various states of undress. Men were into it. But makeup for men stayed mostly unpopular, becoming a benchmark for the separation of women and men in society: it labeled a woman's looks and sexiness as her greatest virtue.

Victorian era

By the time Queen Victoria earned her crown in 1837, The British Library reported that "modest, ringletted prettiness was 'the look'.... Bell-shaped skirts known as crinolines became wider and wider, needing ever more petticoats, and even hooped supports." And, according to The BBC, ladies were getting in formation "in the home, as domesticity and motherhood were considered by society at large to be a sufficient emotional fulfillment for females." The pale, frail, weak look was all the rage. No particular body part was emphasized — just so long as a women didn't look too hearty or strong. According to artist and researcher Alexis Karl, "Consumptives were thought to be very beautiful." Who knew that dying of tuberculosis would make you the hot chick?

Makeup of the time was also incredibly dangerous. Lead, ammonia, mercury, and nightshades were common ingredients. And the Victorian's weren't completely ignorant of the effects of these poisons. Women were simply willing to poison themselves in order to look more beautiful. Of course, male-dominated desire favoring weak, submissive women sparked the trend, so it wasn't like ladies all decided to kill themselves to look pale just for the heck of it.

The turn of the century

The 1890's brought about the Gibson girl. The Gibson girl was an illustration by Charles Gibson that defined a beautiful woman of the age. From the turn of the century to the beginning of World War I, women everywhere tried to match the drawing. She was pale, though not as powdered as previous years. She wore a tight corset, but the dresses were cut to show more of her figure (her real figure — plus a bustle of course).

A large bust was preferred, and, though it was still popular for girls to look a little soft and round, the trend towards a thinner ideal was beginning. The Gibson girl wasn't actually a real person, but Evelyn Nesbit, considered to be the world's first supermodel, was the closest match. But it was a case of yet another standard of beauty invented by a man's drawing, rather than inspired by any existing woman.

The 1920s

By the end of the 1910s, many women were hitting the workforce during World War I. And after the war? They weren't about to give up all that independence. In 1920, women scored the right to vote — and they weren't going to take the piled-up hair and corsets anymore! Flappers brought about a complete change in fashion and body type. Since they were gaining a taste of men's power, the ideal women's body became a more boyish figure. For the first time, the curvy, fertile look was completely out. Girls wanted to look thin with no curves, and they were chopping their hair.

Skirt hemlines were hiked up higher than ever, allowing women to move, dance, and finally have some fun. The flip side of the flapper movement? It's where our serious modern obsession with weight began. Before the '20s, it was difficult to weigh yourself unless you were very rich. Full length mirrors were also incredibly expensive, so only the wealthy had ever even seen their entire bodies. But, as bathroom scales were invented, it became very simple to notice exactly how thin or big you were. The rise of department stores also gave working class women a chance to finally see all of themselves at once. That also meant they could see all of their flaws, thus igniting our contemporary version of body obsession.

The '30s and '40s

Unfortunately for flappers, the '20s ended badly and the Great Depression made fashion an afterthought. Most women weren't able to worry about having a skinny figure and the perfect clothes, so the ideal body type became slightly more full.

Because of a lack of resources, and then the rationing of World War II, women had to get creative with their clothes. They would rework men's suits into women's attire. That brought about the padded shoulder look (not quite to the '80s extreme, but close), creating a sharp hourglass figure. Women were recovering from years of a terrible economy, along with food rations for the war, and the ideal body type mirrored that. Nobody wanted to look stick thin — it seemed too close to starving — but a voluptuous figure was also unrealistic for the time.

The '50s to early '60s

The depression and World War II were history, and America was making a lot of money for the first time in years. People were in the mood to celebrate, and with that indulgence came a slightly fuller figure. The hourglass figure was sought after and having a large bust was strongly encouraged.

Now, a lot of people think that the sex symbols of the '50s would be considered plus sized now. Though they are certainly heavier than the models of today, the movie stars were still very thin — they just had boobs. Most of the glamour girls of film had a BMI between 18.8 and 20.5, much lower than the average women's BMI of 23.6. So, even at a modern time where the ideal woman was a little bigger, she was still thinner than most real girls. In this newsreel clip from the early '60s, a town holds a "Miss Fat and Beautiful" contest. To modern ears, it's pretty shocking to hear a bunch of ladies being openly called "fatties". And by today's standards, these women aren't that big! Clearly, the demand for thinness has been around for quite a while.

The late '60s to the '90s

By the '60s, the culture began to shift. People weren't happy just to have a house and car, sitting at home as a housewife. Young people rebelled against the constricting ways of '50s, and with Twiggy becoming the most famous model of the age? Thin was (back) in.

The '70s saw greater freedom for women, but skinny was still the ideal. Farrah Faucett may have had a larger bust than Twiggy, but she was still rather petite. Makeup and fashion tilted toward a more natural look. Looks weren't as bold as the swinging '60s and hair was worn natural and very long.

When the '80s rolled around, the Supermodel era began. Women were meant to be tan, tall, thin, but slightly athletic. Hips got much smaller, though large breasts were still the rage. Women were influenced more by models than actors for fashion and body trends, while models continued to be wildly thinner than the average person.

Just when it seemed like the ideal body couldn't get any thinner, in came the '90s. Kate Moss came along to give Twiggy a run for "skinniest model of all time". The Brit model with a BMI of 16 and that famous "heroin chic" look became popular. Funny that both the '90s and the Victorian era modeled good looks after people who were, quite literally — dying. With waif models in vogue, the '90s presented the thinnest feminine ideal in history.

What really is 'perfect'?

Luckily we're stepping into an age where the media is beginning to celebrate diversity of race and body type — though there's still a long way to go. Before New York Fashion Week 2017, the Council of Fashion Designers of America sent out a memo to remind designers to seek out healthy models and a wider range of types saying, "New York Fashion Week is also a celebration of our city's diversity, which we hope to see on the runways."

The thing to remember is most of the historical standards of beauty were based on a drawing or a painting of a man's fantasy! Nowadays Photoshop has the same effect, making already-petite models look unattainably perfect. You can't possibly live up to a fictional piece of art or a masterfully altered photograph. Since standards have changed so much over history (just try to wear big 80s hair and makeup to look hot today), it proves that these standards are really just temporary ideals.

If your body isn't considered "perfect" today? Who cares! "Perfect" is an illusion that no one can attain. So, be happy with the body you have and celebrate all the things that make up your gorgeous, imperfect self.