Inside Pauli Murray's Inspiring Activist Career

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

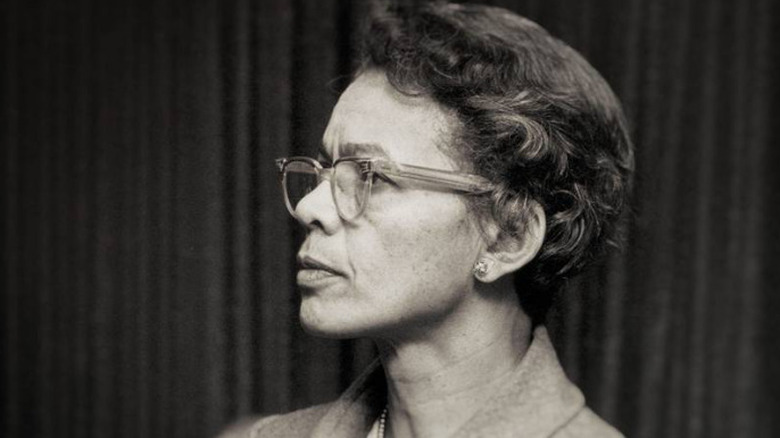

American civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks might be household names, but there's another inspiring activist you've probably never heard of: Pauli Murray. Born Anna Pauline Murray in Baltimore in 1910, Murray didn't have an easy childhood. According to The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, her mother died when Murray was only 4 years old, and her father was murdered in 1923, making her an orphan at just 13 years old. When writing about her early years, Murray said, "The most significant fact of my childhood, was that I was an orphan" (via the Philadelphia Gay News).

Despite a rough start in life, according to the Smithsonian Magazine, Murray went on to earn multiple degrees and become a successful author, attorney, professor, priest, and even an Episcopal saint, all while helping change U.S. laws for racial and gender equality. Although she's not as widely known as some other figures in the civil rights movement, Murray has made no less an impact on the world. Here, we take a look at this incredible leader's legacy of activism.

Pauli Murray was rejected by a university that later decided to name a building after her

After graduating from Hunter College with an English literature degree in 1933 (via the New York Daily News), Pauli Murray set her sights on the University of North Carolina (UNC)'s graduate program in sociology. But, according to the UNC history department, Murray received a letter saying she was not allowed admittance because of her race. In Murray's own words, shared by WUNC North Carolina Public Radio, she talked about her controversial decision to apply to UNC. She said her application "was met with consternation by my family, my immediate family, primarily because they were afraid that they would be lynched, or that the house would burn down." Murray fought the rejection, enlisting the help of the media and approaching the NAACP, which told her that her case would not win, according to WUNC.

Eighty-two years later, several departments at UNC helped lead the charge to rename a building on campus after Murray. In a 2020 letter to the university's chancellor, the heads of four departments made a case for renaming a building called Hamilton Hall (after Joseph Grégoire de Roulhac Hamilton, a known white supremacist) to Pauli Murray Hall. "Naming our building after her will serve as a reminder of what is lost, what could have been, and what can be as we move forward," the letter stated. Although an official decision has yet been made, the history department already uses the name.

She refused to move to the back of the bus before Rosa Parks did

Rosa Parks is a household name for standing up to segregation laws that required Black people to sit in the back of buses, but what most Americans don't know is that Pauli Murray did the same thing 15 years earlier. According to a 1940 article in The Carolina Times, Murray and her friend, Adelene McBean, were traveling on a Greyhound bus to Durham, North Carolina, when McBean was in pain from the uncomfortable seat. Murray approached the driver, asking if two white children could move forward so they could sit in the children's seats. After the driver pushed Murray and told her to sit down, Murray moved forward two rows after other passengers got off at a later stop. When the driver shouted at them to move back, Murray reportedly "let go a machine gun fire of questions concerning the policies of the Greyhound Bus Lines."

After refusing to move, the women were arrested, per The Carolina Times. However, when the NAACP tried to fight their case as unconstitutional, the state of Virginia got crafty. In a 1976 interview, Murray said, "When the state discovered that the NAACP was going to challenge and probably use this as a test case, it withdrew the charge of the segregation statute and left standing the creation of a disturbance." The experience pushed Murray to enroll in law school "with the single-minded intention of destroying Jim Crow," per The Guardian.

She defied gender norms at a time when few women did

Pauli Murray fought for racial and gender equality throughout her life but found it difficult to conform to the traditional gender roles of her day. While Murray identified as a lesbian and had relationships with women, she struggled with her gender identity, even being hospitalized for her mental health, per the Philadelphia Gay News, which stated that Murray was "devastated" to learn she had no hidden male organs, as she had long suspected. Murray also tried unsuccessfully to take male hormones, per The New Yorker.

Murray dressed in an androgynous style and "variously identified as a woman, a man and as neither," per the Philadelphia Gay News. Even as a child, she used the male nickname "Paul" before eventually going by "Pauli" in favor of her given name, Anna (via The New Yorker). She remained fluid with pronouns, noted The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, which stated she "used the phrase 'he/she personality' in correspondence with family members during the early years of their life." However, Murray used she/her/hers pronouns in her published works. And, according to author Brittney C. Cooper, Murray eventually identified as a woman after years of resistance (via The Center).

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Eleanor Roosevelt became a lifelong friend of Pauli Murray

In the wake of a rejection from the University of North Carolina, Pauli Murray had a bone to pick with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. According to The Guardian, Murray put pen to paper after Roosevelt visited the university and commended the institution for "its liberal values." While the president didn't respond to her letter, which expressed disappointment about his lack of support for civil rights, his wife, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, did. "I understand perfectly, but great changes come slowly," she wrote to Murray, per The Guardian.

Their written correspondence struck up a friendship, and the pair remained close over the years — The Boston Review noted that a book was even written about their relationship called "The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice" by Patricia Bell-Scott. "The two women quickly found the means to push their respective agendas forward through their mutual social interaction," noted the publication, adding that Roosevelt "made a point of interacting socially with African Americans, servants, sharecroppers, and miners in ways that scandalized traditionalists and dramatized inequality." Roosevelt's connection also led Murray to teach at Brandeis University in the late 1960s through early 1970s, where Roosevelt was a longtime faculty member and trustee (via Brandeis Now).

Pauli Murray experienced gender discrimination at law school

Determined to become a civil rights lawyer, Pauli Murray applied to the Howard University School of Law. While race wasn't an issue (Howard is a historically Black university), Murray was the sole woman in her class and even among the all-male faculty (via The New Yorker). She became the first woman to graduate from the university with a law degree and wrote in her memoir (via the ACLU) that it was then when she "first became conscious of the twin evil of discriminatory sex bias."

When Murray applied to Harvard Law School for graduate studies, she received a similar letter to the one she received from the University of North Carolina, according to The New Yorker. This time, Murray was rejected because she was a woman, not because she was Black. Her response: "I would gladly change my sex to meet your requirements, but since the way to such change has not been revealed to me, I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds on this subject."

Instead, Murray attended the University of California at Berkeley for a master's degree in law, worked at a New York law firm, and later moved to Ghana to lecture at the Ghana School of Law, per The New Yorker. Upon returning to America, Murray smashed another glass ceiling: becoming the first Black female to receive the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science from Yale University (per the ACLU).

The activist often spoke out against the concept of 'separate but equal'

A key point used to uphold segregation was the idea of "separate but equal," which was declared constitutional in the 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson (via Time). In theory, the concept should have meant Black people would have different, yet similar, facilities and accommodations as their white counterparts. However, in the documentary "My Name is Pauli Murray," Pauli Murray recalled the rickety, run-down school she and other Black students attended versus the tidy lawns of the nearby school for white children. She said that the act of separation in itself "do[es] violence to the personality of the individual affected," according to The Washington Post, which also noted that Murray challenged segregated restaurants 17 years before lunch counter sit-ins gained widespread press attention.

While attending Howard University, Murray and a group of students stopped by the Little Palace Cafeteria, a whites-only restaurant in Washington, D.C. Although staff wouldn't serve them, Murray and her friends "took out their books, settled in and had class," The Washington Post noted. Though the owner closed the restaurant for the day after more students showed up, just days later, the restaurant owner changed its segregation policy. According to the publication, Murray continued to speak out against segregation and the idea of "separate but equal," even making it the topic of her history-making final paper at Howard University.

Her work contributed to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the end of segregation in schools

While preparing her final law school paper, little did Pauli Murray know that it would help lead to the end of segregation in U.S. schools. According to The Washington Post, one of Murray's former professors pulled the paper out when working on Brown v. Board of Education, the iconic Supreme Court case that outlawed segregation in American schools. Although a college thesis, Thurgood Marshall and his legal team used some of its ideas to overturn the constitutionality of "separate but equal" (via USA Today).

Murray's activism contributed to another landmark case: the 1964 Civil Rights Act. According to Forbes, Murray fought back against Congress, which was, at the time, "bitterly divided over a single word in the most important piece of civil rights legislation in a century": the word "sex." Murray wrote how, without it, Black women could still be fired over their gender, even if they were protected because of their race, as "these two types of discrimination are so closely intertwined" (via Forbes). After Lady Bird Johnson, the First Lady at the time, showed Murray's influential memo to then-President Lyndon B. Johnson, the term "sex" remained in the final bill — something all women today owe, in part, to Murray.

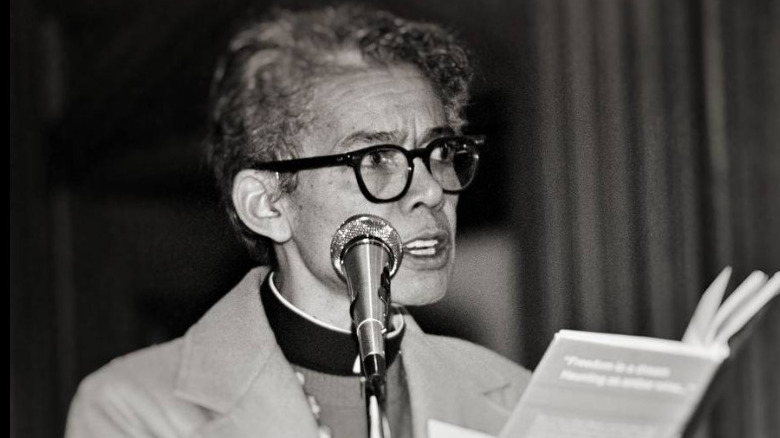

Pauli Murray was a prolific writer of works that inspired hope and change

Writer is among the many titles Pauli Murray held during her incredible life, and, from diaries and letters to papers, articles, memos, and books, Murray penned her thoughts on civil rights and her own life, too. One of her most influential works was "States' Laws on Race and Color," a 746-page book she wrote on behalf of the Methodist Church (via The New Yorker). The church opposed segregation and wondered "when they were legally obliged to adhere to it and when it was merely custom." Thurgood Marshall called the work — which The New Yorker said revealed "both the extent and the insanity of American segregation" — a "Bible for civil rights lawyers," per the Poetry Foundation. The book, like her college thesis, also played a part in the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, per The New Yorker.

In addition to her civil rights writings, Murray published two memoirs: "Proud Shoes," published in 1956, and "Song in a Weary Throat," released two years after her 1985 death (via the Citizen Times). She was also a poet, who, according to the Poetry Foundation, authored a collection of poetry in 1970 called "Dark Testament" and wrote various works, including a serialized novel, which was featured in various publications. Her poetry, like her activism, included messages of change and hope. For example, in "To the Opressors," she wrote: "But ours is a subtle strength Potent with centuries of yearning."

Pauli Murray inspired other female activists like Ruth Bader Ginsburg

With all the important work Pauli Murray did in her lifetime, it's no wonder she inspired other activists. One of these women went on to become one of the most prominent legal minds in America: the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In a video shared by Time, Ginsburg discusses how Murray helped her when writing a brief for the Reed v. Reed case in 1971, "the first time the nation's highest court recognized women as victims of sex discrimination."

In the video, Ginsburg said she first met Murray in 1958 while working as a summer associate at the firm where Murray was the only female attorney. Although they never worked directly together, Ginsburg was inspired by Murray's idea that the text of the 14th Amendment should be interpreted literally, meaning states couldn't deny equal protection to "any person," not any male person. Ginsburg and the team working on Reed v. Reed used Murray's idea in arguing the case, leading the Supreme Court to rule that "a sex-based classification law was unconstitutional."

Ginsburg said she added Murray's name to the cover of the Reed v. Reed brief, even though Murray had already moved on to divinity school at the time. Ginsburg went on to praise "her willingness to speak out when society was not prepared to listen" (via Time).

The civil rights leader was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women

By 1965, Pauli Murray had been appointed to the President's Commission on the Status of Women by John F. Kennedy and was working as a professor at Yale University (via NOW). Murray was upset about The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's segregated job advertisements, categorizing jobs according to gender. Betty Friedan, author of the famed book "The Feminine Mystique," reached out to Murray. While attending the Third National Conference of Commissions on the Status of Women in Washington, D.C., per NOW, a meeting in Friedan's hotel room, including Murray and other attendees, led to the establishment of the National Organization for Women, or NOW.

In 1966, the organization got its official start, with the first NOW Organizing Conference. However, according to The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, Murray eventually distanced herself from the group because she "did not believe that NOW appropriately addressed the issues of Black and working-class women."

After her death, she was named an Episcopal saint

Pauli Murray achieved many firsts in her life — one of the last was becoming the first Black female priest in the Episcopal Church, just several years before her 1985 death. She was called to ministry late in life and didn't go to seminary until she was in her 60s, prompted by the death of her longtime partner, Irene Barlow (per The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice). Speaking of her "unrelenting desire to seek the next great thing," Betsy West, co-director of the film "My Name is Pauli Murray," told The Sacramento Observer about Murray's decision to pursue priesthood even though the Episcopal Church had never allowed female priests. Never one to shy away from a challenge, according to West, Murray did it anyway.

In 1979, Yale Divinity School granted Murray an honorary degree (fun fact: Yale also named a residential college after Murray). Interestingly, per USA Today, "Murray never wrote about the church's position on homosexuality — at least not publicly." However, she did write a scathing letter (which she never sent) to a bishop in the church "who had been saying homophobic things," according to West.

In 2018, Murray was permanently added to the Episcopal Church's calendar of saints, and an icon of her resides in St. Thomas' Parish in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. Today, Murray's legacy "continues to inspire new generations of 'firebrand' leaders to authenticity and activism" in the church (via the Episcopal News Service).

The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice honors her legacy

While Pauli Murray died of cancer in 1985, her activism lives on through the work of The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, based at her childhood home. The National Park Service recognized the house, located at 906 Carroll Street in Durham, North Carolina, as a National Historic Landmark in December 2016 (via the National Park Service). According to The Center's website, "only 2% of the 95,000 entries in the National Register of Historic Places focus on the experiences of African Americans."

The Center aims to change this by providing an example to those "who want to know, share and lift up the accomplishments and struggles of women, people of color and queer folk in their communities and this country." In an interview for The News & Observer, Barbara Lau, executive director of The Center, shared that few people actually had heard of Pauli Murray. According to the publication, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation granted The Center with $1.6 million in September 2021 "to help further highlight Murray's vision, activism and scholarship."

A 2021 Amazon Prime documentary tells the story of Pauli Murray's inspiring activist career

In 2021, Pauli Murray entered households around the world when a documentary about her life, "My Name is Pauli Murray," was released on Amazon Prime. The documentary follows Murray's life of activism, starting at her death, when Murray's niece learns the incredible accomplishments her aunt never shared with her (via Capital and Main). Directors Betsy West and Julie Cohen, who co-directed the Emmy Award-winning documentary "RBG" in 2018, felt "flabbergasted" that they heard about Murray for the first time from Ruth Bader Ginsburg, according to USA Today. Fortunately, according to the newspaper, the directors had no problem finding enough material for the film, however, due to Murray's extensive record-keeping including "personal papers and writings, as well as more than 800 photos, 40 hours of audiotaped interviews and some video."

Deadline summed up the reaction of the directors and of countless others: "Why did I not know about Pauli Murray?" The sentiment was shared by USA Today reporter David Oliver, who was also "furious" he'd never heard of Murray until watching the documentary and interviewing the directors — whose experience of making the film led them to consider others whose stories have remained untold. When it comes to "who we revere, whose contributions, particularly intellectual contributions, have advanced the country," Cohen told Deadline, "Pauli Murray's just a fantastic example of someone whose history hasn't been explored enough and needs to be learned more."